Revisiting Alcohol Pricing Policies for Healthier Lives

This piece is part of a two-part blogpost series. To read about published learnings from alcohol policies, please click here.

Authors: Marion Devaux, Céline Colin, Bert Brys and Michele Cecchini

Public health policies such as increased alcohol prices, drink and driving restrictions, public communication and advertising restrictions are cost-effective measures to promote a healthy lifestyle. However, alcohol policy decision-making does not occur in a policy vacuum: it involves complex trade-offs between improving public health, aligning policies with the existing culture and achieving broader economic objectives, especially in countries where alcohol production and trade represent a large share of the economy. The OECD publication ‘Preventing harmful alcohol use’ looks at the health and economic case for governments to upscale alcohol pricing policy as part of a comprehensive alcohol policy strategy.

Purchasing alcohol has become more affordable over the last two decades when changes in real income and the relative price of alcohol are accounted for. In some Eastern European countries such as Lithuania, Romania, the Czech Republic and the Slovak Republic, alcohol affordability doubled or more over the period 2000-2018 because the growth in real income exceeded growth in the relative price of alcohol. An analysis based on 30 European countries and the United States suggests that of the eight countries that saw a decline in the relative price of alcohol between 2013 and 2018, seven did not adjust their alcohol excise tax rate for inflation. Conversely, countries adjusting alcohol excise duties for inflation experienced either no change or an increase in the relative price of alcohol.

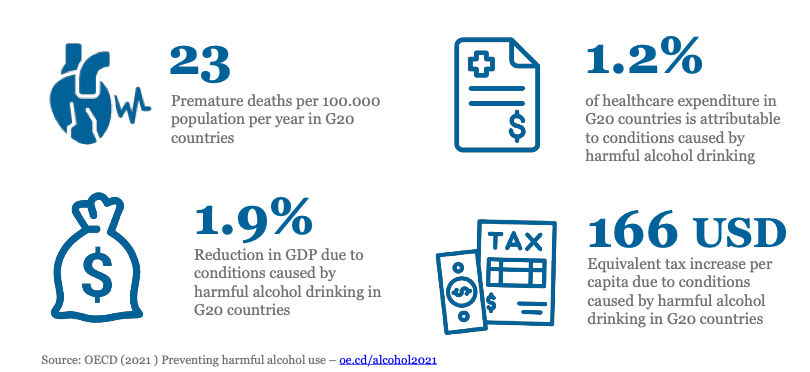

Harmful use of alcohol is a top public health priority with wider economic effects (see infographic 1). Harmful patterns of alcohol consumption are widespread across population groups, with one in five adolescents having experienced drunkenness, and 22% of adults consuming six or more drinks per drinking session on average in the G20. Harmful alcohol consumption is responsible for medical conditions such as alcohol dependence, cancer and liver cirrhosis, as well as injuries and premature deaths. The cost for treating these conditions equals about 1.2% of total health expenditure each year on average across the G20. For instance, this proportion is estimated about 1.0% in Brazil and 1.1% in South Africa, while it reaches 1.5% in Argentina and 2.6% in the Russian Federation. At the same time, people living with these diseases are less likely to be employed, and when they work, they are less productive. The reduction in workforce productivity due to alcohol-related diseases is expected to make GDP 1.9% lower than it otherwise would be on average across G20 countries annually over the next 30 years. The greatest negative impact on GDP (up to 4.5%) is expected in Latvia, Lithuania and the Russian Federation.

Infographic 1. The burden of harmful alcohol consumption in G20 countries

Better harmonisation of taxation policies across different products and ensuring adjustment for inflation are priorities for effective alcohol pricing policies. Across 50 countries studied, 80% tax all beverage types, while 20% tax only beer and spirits. While, for instance, Brazil and China tax all beverage types, Argentina does not tax wine. An even more striking finding is that 74% of countries do not automatically adjust alcohol taxes for inflation. This is a major driver of the increased affordability of alcohol over recent years. Many of the most effective policies to tackle excessively cheap alcohol have not been implemented in most countries. For instance, minimum unit pricing (MUP), which sets a “floor price” for an alcohol unit, has been implemented in only a few high-income countries such as Canada (at the subnational level), Scotland and Wales. MUP is an interesting instrument to increase the price of low-priced alcohol, which is disproportionally consumed by those who drink heavily. Another advantage of MUP is that the evidence shows that it effectively reduces alcohol purchases in households who purchase the most alcohol.

Raising alcohol pricing may play a key role in the alcohol policy for countries that seek to improve health and boost the economy. The OECD examined alcohol-pricing policies with other public health interventions ranging from health information to policing, including health care and regulatory policy. Pricing policies, namely taxation and MUP, are the most effective and cost-effective interventions as they generate savings in health expenditure that are greater than the cost of implementing the policy.

Increased alcohol taxes could play an important role in helping countries make progress on the sustainable development goals (SDGs), especially in developing countries. For example, pre-COVID OECD work on Côte d’Ivoire showed that changes in alcohol taxes could play a significant role in mobilising domestic resources. While the taxes on beverages raise more revenues than tobacco taxes in Côte d’Ivoire, the country has ample scope to increase the alcohol tax revenues. Although excise duties on alcohol have been regularly increased in the past, aligned with the 15%-50% range agreed within the West African Economic and Monetary Union, they could be increased further in particular for beer and cider.

Alcohol tax revenues can play a significant role in closing the health sector financing gaps that have appeared during the COVID-19 crisis. In order to ensure adequate funding for their health care sector, countries may wish to softly earmark alcohol tax revenues. For example, in Côte d’Ivoire, little tax revenue is earmarked for health. Earmarking, however, must not be a substitute for broader tax reform to increase the overall level of tax revenues. Moreover, if Côte d’Ivoire were to start earmarking tax revenues for health, the success of such a strategy would depend upon several conditions, including ensuring an alignment of the health policy objectives across all of government, including the Ministries of Health and Budget.

Raising alcohol prices is cost-effective and provides an excellent return on investment, but it also requires government to make difficult trade-offs regarding the impact on the economy and the labour market, for instance. Government will also have to decide which type of alcohol consumer its alcohol policies are targeted to. Pricing policies, despite being highly effective and efficient, affect both consumers who drink at low to moderate levels and those who consume alcohol heavily. Policy interventions targeting only people who drink heavily (e.g. such as screening and treatment) have a significant impact on those people, but have a smaller impact on the total population and are more expensive.

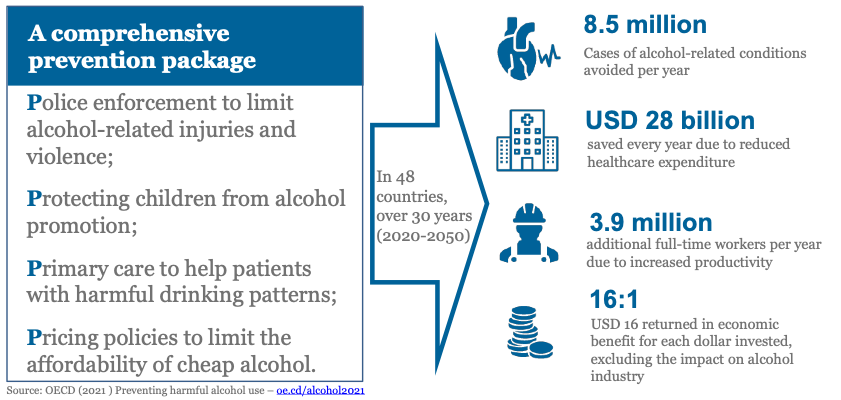

To overcome this challenge, countries need comprehensive policy packages that addresses multiple dimensions, rather than single policies that are implemented in isolation. For instance, the OECD evaluated a comprehensive PPPP policy package that includes: Protecting children from alcohol promotion; better Police enforcement to prevent alcohol-related traffic injuries; strengthening Primary care to help patients with harmful patterns of alcohol consumption; and strengthening Price policies to limit the affordability of alcohol, particularly for cheap alcohol. Such a policy package would avoid 8.5 million cases of alcohol-related diseases every year across the 48 countries studied, and would reduce health expenditure significantly[1]. For instance, this policy package would help Brazil save each year USD PPP 609 million in health care expenditure. This amount equals USD PPP 2 146 million in China, USD PPP 438 million in India, USD PPP 956 million in the Russian Federation, and USD PPP 121 million in South Africa. Overall, for every USD invested in this policy package, USD 16 will be returned in economic benefits due to improved productivity. A strong case can therefore be made to embed alcohol price increases within broad policy packages that improve public health and bring large economic gains to our societies (see infographic 2).

Infographic 2. Potential effects of a PPPP policy package, per year in 48 countries

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed and arguments employed herein are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official views of the OECD or of its member countries.

[1] OECD, 2021. Preventing harmful alcohol use

0 Comments