Health Earmarking in the Philippines

Health Earmarking in the Philippines

Practitioner Perspectives: A JLN Blog Series

By Val Gilbert Ulep1, with contributions from Ish Pargas2 and Art Alcantara2

This piece3 is one in a series of blog posts reflecting health financing practitioner perspectives on domestic resource mobilization (DRM) reforms in their countries and the local dynamics around health financing. This work stems from the Joint Learning Network’s Dynamic Inventory of DRM Efforts. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this work reflect the views of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the World Bank, its Board of Executive Directors, or the governments they represent. Please contact [email protected] if you have experiences from your country that you would like to share!

Woman receives a health check-up in Agusan del Sur, Philippines.

Source: Dave Llorito/World Bank

The Philippines started its path toward universal health coverage (UHC) in 1969 with the creation of an early Medicare health insurance scheme, where direct payments were made to accredited providers or to patients for reimbursement (Table 1). After decades of implementation, more than half the population remained without health coverage,4 prompting the creation of the Philippines Health Insurance Corporation (PhilHealth) in 1995—a parastatal entity tasked with managing delivery of a costed benefits package to all citizens through a mix of premiums, user fees, and government subsidies for the poor. PhilHealth has progressively expanded to cover a greater number of services for larger segments of the population, with Sin Taxes providing an avenue to drive expansion in fiscal space for health.

The 2012 Sin Tax Law, one of the most lauded health legislations in the Philippines in recent years, brought about necessary reforms to tobacco and alcohol taxation. The law increased excise taxes on alcohol and tobacco and simplified the outdated excise tax regime. Considered as both a health and fiscal measure, the law aimed to reduce the high prevalence and improve commensurate health impacts of smoking and alcohol consumption in the country, while at the same time, increasing financial resources for the health sector through earmarking.5

Between 2012 and 2018, earmarking increased the budget of the Department of Health by almost fourfold in per capita constant terms. Today, Sin Taxes continue to provide on average approximately 50 percent of the total health budget.

| Table 1. Health System Performance and Financing Indicators | ||

| Population (millions, 2019) | 108.1 | |

| Life expectancy (2018) | 71 | |

| Fertility rate (total births per woman, 2018) | 2.6 | |

| Human Capital Index (HCI) score, 2020 | 0.52 | |

| GDP per capita (current US$, 2019) | 3,485.08 | |

| Current health expenditure (CHE), 2018 | Per capita (US$), | 137 |

| Share of GDP (%) | 4 | |

| Share of CHE (%): | ||

| Domestic government | 33 | |

| External health expenditure | 1 | |

| Social Health Insurance | 13 | |

| Out-of-pocket | 54 | |

| Share of total government expenditure (%) | Health (2018) | 7 |

| Education (2009) | 13 | |

| Military (2019) | 4 | |

Source: Macro statistics from World Development Indicators (2009, 18, 19). Health expenditure data from WHO Global Health Expenditure Database (2018). Human Capital Index (2020)

Note: Data in Table 1 downloaded on April 15 2021. HCI score from September 2020 includes measures of survival, education, and health. See HCI for further details.

Structure of PhilHealth.6 PhilHealth operates within a devolved health system, where local government units (LGUs) have full autonomy to plan, manage, and implement health programs and services according to priorities, using a mix of local tax revenue and block grants financed by the Department of Budget and Management (DBM). Only 30 percent of facility bills are covered by PhilHealth, while the rest are financed by LGUs at the primary and secondary care levels, and through out-of-pocket (OOP) payments. As of 2020, 85 percent of the population was covered by PhilHealth as a result of compulsory enrollment,7 of which 40 percent are poor populations whose premiums are covered by the government. However, there is a persistent gap of approximately 20 percentage points between coverage rates reported from the national government and those reported through household surveys, indicating that many who are theoretically entitled to free care do not know of this entitlement.8

The benefits package offered by PhilHealth is structured via a positive list of included services and terms of payment that are established centrally.9 However, both the Department of Health (DOH) and LGUs offer further benefits to citizens, leading to a lack of harmonization between what is offered via the premium and tax-funded systems. Finally, there is a Sustainable Development Goal (SDG)–related benefits package, which covers a set of services including malaria, HIV/AIDS, and family planning. A discreet list of pharmaceuticals is also included under PhilHealth, with 18 drugs listed under outpatient benefits.10 However chronic shortages, poor outpatient coverage, and consumption of non-prescription drugs push users toward OOP.

While payments by PhilHealth to providers are mostly outputs-based (all-case, rate-based for inpatient hospital costs; capitation for public health and ambulatory services), there is also fee for service for hospital outpatient services. Case rates are meant to form a hard constraint driving average costs below this rate; however, most facilities end up creating their own fee schedules and billing the patient the difference between the case rate and what they set. While poor patients face zero copayment and are covered at 100 percent of the facility bills, providers also bear little financial risk and have low motivation to operate efficiently.11

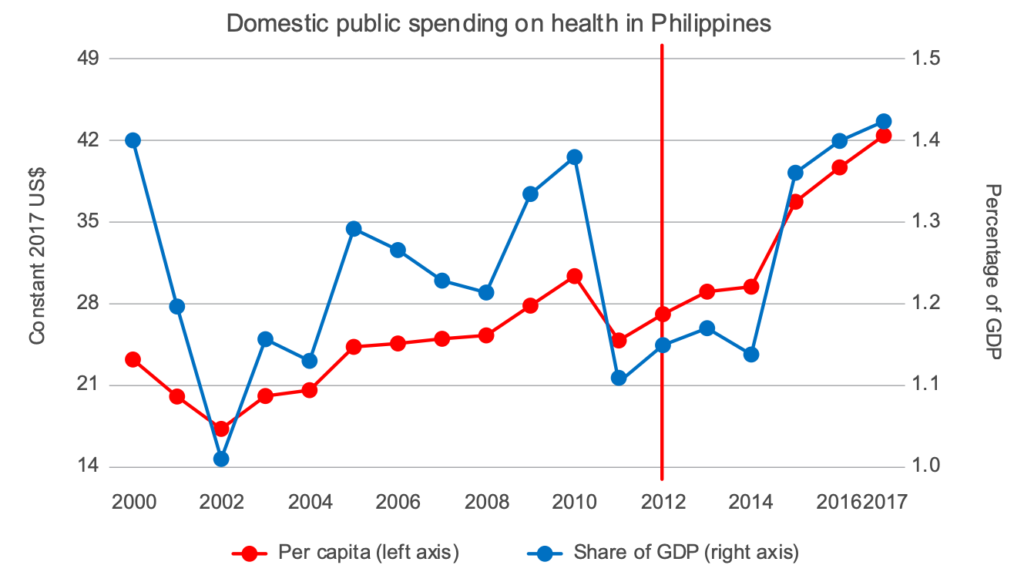

Figure 1. Domestic Public Funding Trends for Health per Capita and as a Share of GDP

Source: Author’s calculation using data from WHO Global Health Expenditure Database.

Note: Vertical red line indicates when Sin Tax Law was enacted.

Domestic resource mobilization reform. Nearly 100 percent of current health expenditure in the Philippines comes from domestic resources. However, despite the existence of National Health Insurance, more than half of all current health expenditure remains OOP. The motivation for domestic resource mobilization (DRM) reform within the Philippines was thus twofold. First, within PhilHealth, a persistent challenge included securing funding to cover premiums for vulnerable groups. Second, smoking is a persistent issue in the Philippines, with a burden on population health and the health system. Before 2012, tobacco products in the Philippines were cheap—sold at approximately US$1 per pack or less—making them affordable and accessible even to young and poor populations. Approximately 30 percent of adults were smokers, and the poor were twice as likely to smoke than their rich counterparts. The cheap price of tobacco products was attributed to the “broken” excise tax regime. Government revenues from tobacco excise taxes were declining as a share of gross domestic product (GDP): from 0.9 percent of GDP in the 1990s to less than 0.5 percent of GDP in 2012.

The Sin Tax Law (RA 10351) helped to address both of these issues by taxing tobacco products as a way to reduce consumption improve population health, as well increase the allocation of public resources for health and the poorest populations in particular. Passed by the Philippine Senate and House of Representatives during President Benigno Aquino’s tenure, this earmarking reform was motivated by the president’s dual platform to introduce no new taxes and achieve universal health coverage (UHC).12 The health earmark is considered “soft” because annual allocations are still decided through the budgetary process and reviewed on a regular basis, instead of as “hard,” which are legislated amounts that are not subject to annual review. Framing the tax reform as a health measure was critical to its passage: the Department of Finance (DOF) was willing to accept this soft earmark due to multiple safeguards being put in place and ultimately to support fiscal expansion, as well as to reduce tobacco and alcohol consumption and improve health coverage. The law set the floor price for all brands of cigarettes and alcohol, removing a price classification freeze, and raised the minimum tax rate by four times of pre–reform levels. It also moved from the multitiered ad valorem system to a specific structure with only two tiers13 –converging in a unitary rate over four years– and included indexation to account for inflation with prescribed periods of increase.

Health earmarking was a key feature of the Sin Tax Law, but with different nuances by product. For alcohol, 100 percent of incremental revenue was allocated to PhilHealth. For tobacco tax, approximately 85 percent of incremental tax revenues was allocated, after 15 percent was deducted for tobacco-farming provinces in northern Philippines. From both sources, 80 percent accounted for the premium subsidy of poor households through the National Health Insurance Program (NHIP) and programs to support health-related Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) of the Department of Health (DOH), while the remaining 20 percent was allocated to the DOH Medical Assistance Program and the Health Facilities Enhancement Program (HFEP).

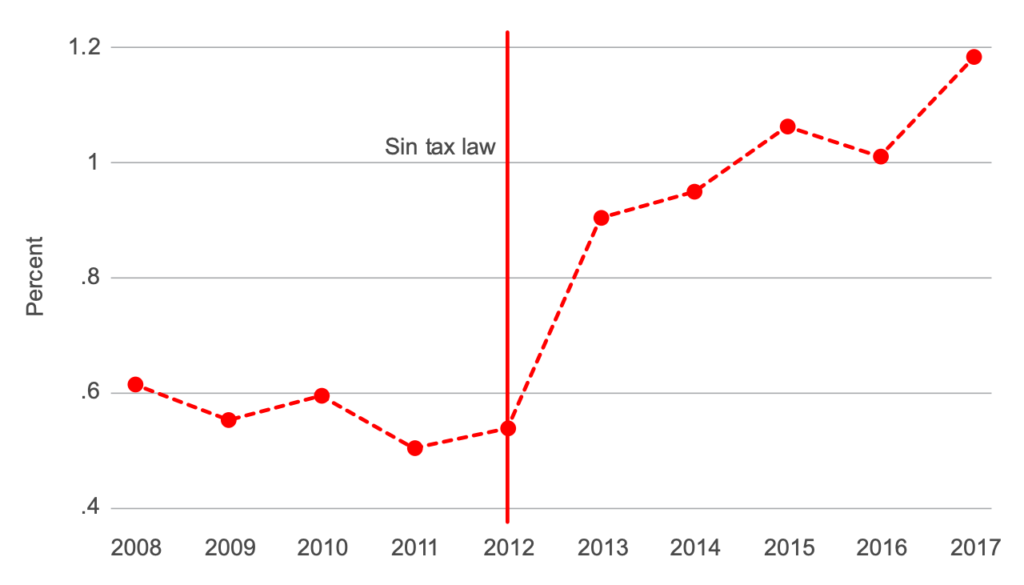

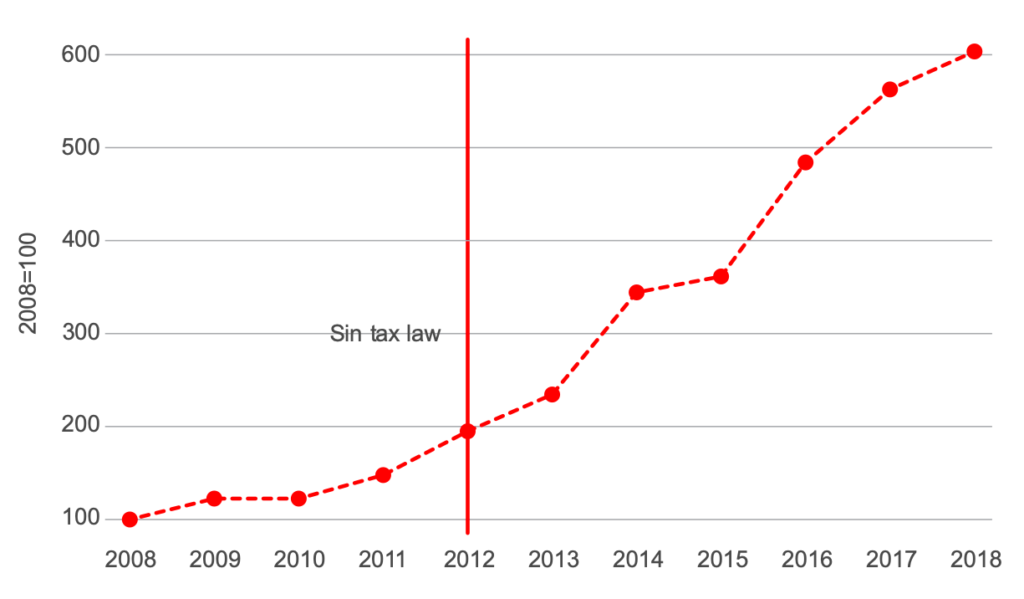

Revenue impacts. Against the original objectives of increasing resources for health and decreasing the prevalence of smoking, the Sin Tax Law was successful. The tax revenue collected from tobacco and alcohol products doubled from 0.6 percent of GDP in 2012 to 1.2 percent of GDP in 2017. Earmarking increased the budget of the Department of Health by almost fourfold from 2012 to 2018, in per capita constant terms. On average, about 50 percent of the total DOH budget came from the incremental excise tax revenues (Table 3 Figures 2 and 3). A recent decomposition model indicates that public spending on health per capita increased from US$20 before the Sin Tax Law to about US$41 in 2016.14 This increase in public spending per capita can be largely attributed to the increases in reprioritization and aggregate public spending as a result of health earmarking.

Figure 2. Tobacco and Alcohol Taxes as a Share of Gross Domestic Product

Source: Data from Philippines, Bureau of Internal Revenue, annual reports (various years).

Note: 2018 data are not available.

Figure 3. Budget of the Department of Health (Indexed)

Source: Philippines, Department of Budget and Management. Data adjusted for population and inflation.

A large portion of the DOH budget (67 percent) was used to subsidize the premium of the over–60 population as well as poor households and families in conflict-stricken areas through the NHIP.15,16 As a result, National Health Insurance coverage increased from 81 million before the implementation of the law to 97 million. Additionally, from 2017 to 2018, the DOH was able to introduce new services including vaccinations and TB and other infectious disease treatment, such as for HIV. The budget also allowed for growth of the Health Facilities Enhancement Project (HFEP), including accreditation of 229 health stations, 61 health units and health centers, and 62 public hospitals.17 However, some challenges have persisted. While absorptive capacity has increased the budget execution rate from 54 to 62 percent between 2014 and 2017, there is still room for improvement, with the HFEP at 12 percent—the lowest rate of absorption across programs in 2017.18

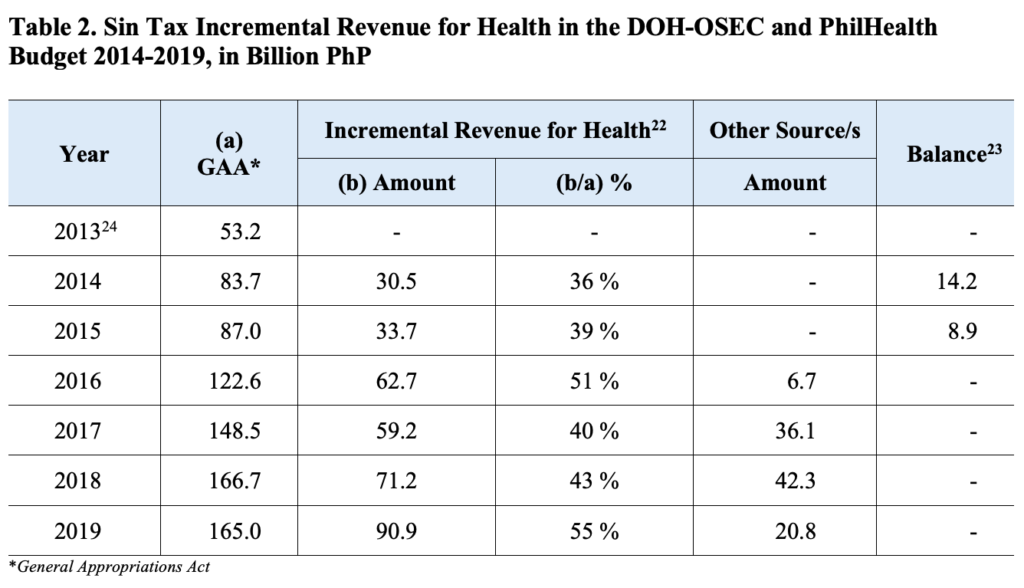

Broader impacts and second wave of reforms. The Sin Tax Law not only continues to increase financial resources allocated to health (See Table 2)19, but also paved the way for adopting tax policies that will curtail the demand for “harmful” products. In 2018, the Philippine Congress passed the Tax Reform for Acceleration and Inclusion (TRAIN) Act (RA 10963), which imposed additional consumption taxes on products such as sugar-sweetened beverages (SSB) and heated tobacco and vaping products. Earmarks on SSB initiated under the TRAIN Act put 30 percent of incremental revenue toward funding social mitigating measures, which include investment in health and targeted nutrition programs. Under the UHC Law passed in 2019 (RA 11223), the national government share from the income of the Philippine Gaming Corporation (50 percent) and the Philippine Charity Sweepstakes Office (40 percent) were also earmarked for UHC. From 2018 to 2019, under the administration of President Rodrigo Duterte, the DOF and DOH lobbied to further amend the Sin Tax Law. DOF argued that despite the increases in tax rates from 2012 to 2018, tax rates for tobacco products were still low, a perception that was echoed by advocates. In 2018, under the TRAIN Act, the tax rate of tobacco products slightly increased from ₱30 to ₱32 (less than $.04) due to a pre-emptive move taken by tobacco industry via a bicameral committee insertion20, with an additional planned annual increase of ₱2.50 until 2024. However, in 2019 (RA 11346) and 2020 (RA11467), the Philippine Congress passed further amendments to the Sin Tax Law, with differential rates for various alcohol and tobacco products.21 For instance, in 2020, the tobacco tax rate for classic nicotine products will be ₱45, with an additional ₱5 annually until it reaches its peak in 2023. After 2024, the incremental tobacco tax for all tobacco will increase by 5% ever year. The alcohol and tobacco earmark was adjusted to total rather than incremental revenues; and by 2020 the corresponding shares earmarked for health were 100 percent from alcohol, 50 percent from tobacco, 50 percent from sugar-sweetened beverages, and 100 percent from both heated tobacco and vaping products.

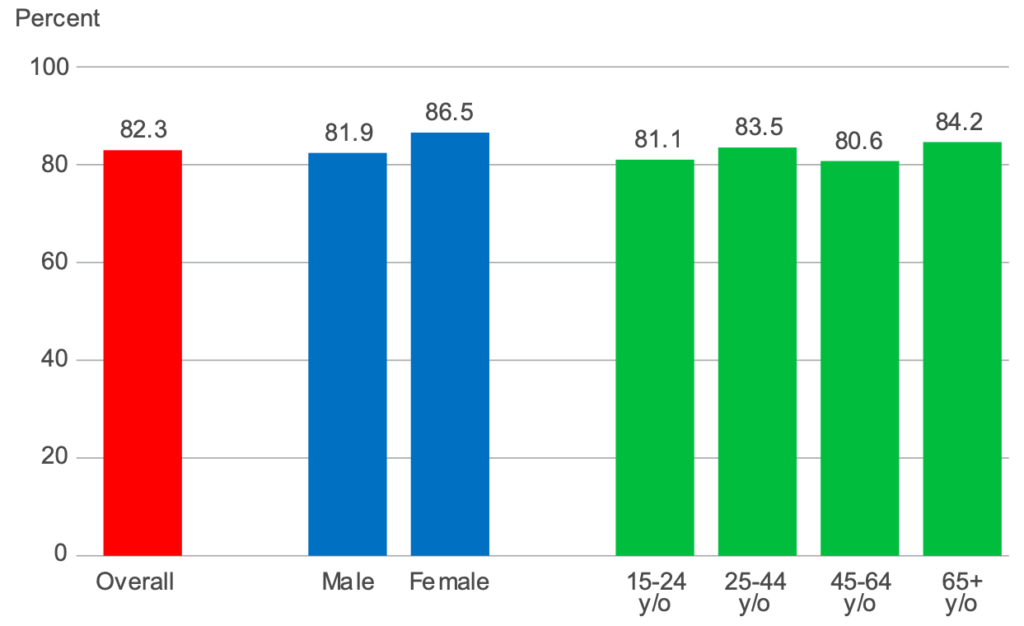

Finally, government surveys indicate that the prevalence of smoking also dropped from 29.7 percent in 2009 to 23.8 percent in 2015, with the decline attributed predominantly to the increase in cigarette prices as a result of increased taxes, and complimented by other control measures (See Figure 4).25

Figure 4. Percentage of smokers who decrease number of sticks because of price increase, by sex and age group GATS, Philippines, 2015

Conclusion. The Sin Tax Law of 2012 has played a critical role in expanding DRM for health in the Philippines, with positive side effects on both inclusion of the most vulnerable populations and impact on negative health behaviors. Linking the earmark to health was critical to its passage. The soft nature of the earmark has been particularly important in ensuring that the earmark can be adjusted and is aligned with regular budgeting processes. Recent lobbying and advocacy efforts have focused on increases to the rate of taxation on tobacco products, which has the potential to provide further revenue to the health system.

With gratitude, we acknowledge guidance and technical review from Jeremias Paul, as well as colleagues in the World Bank who provided input and support: Danielle Bloom, Lauren Hashiguchi, Jewelwayne Salcedo Cain, Netsanet Walelign Workie, Tomo Morimoto, Patrick Hoang-Vu Eozenou, Emiko Masaki, and Maria Eugenia Bonilla-Chacin and the Joint Learning Network’s Domestic Resource Mobilization (JLN DRM) collaborative.

1 Philippine Institute for Development Studies (PIDS)

2 Philippine Health Insurance Corporation (PhilHealth)

3 This narrative updates information provided in the WHO Earmarking working paper: Cashin C., Sparkes S., Bloom D. Earmarking for health: from theory to practice. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017

4 Asia Pacific Observatory of Health Systems and Policies 2018.

5 While the Philippines has reported reduced smoking prevalence related to the tobacco tax and earmark, this note focuses on the fiscal impacts of the law.

6 Asia Pacific Observatory of Health Systems and Policies 2018.Asia Pacific Observatory of Health Systems and Policies 2018.

7 As reported via PhilHealth Stats and Charts for 2020. Registration rate refers to beneficiaries listed in database, and includes members and dependents over the total projected population. Total number of members and dependents for a given year divided by the total population. The World Bank Service Coverage Index puts this number at 61percent for 2017. The number of people spending more than 10 percent of household consumption or income on out-of-pocket health expenditure (as a percentage) has also increased from 3.2 in 1997 to 6.1 in 2012. Accessed on January 04, 2021 at https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.UHC.SRVS.CV.XD.

8 Bredenkamp et al, 2017.

9 The PhilHealth package includes inpatient and outpatient benefits, primary care benefits, and extended primary health benefits for conditions such as diabetes and hypertension. There is also a benefits package that covers financially catastrophic conditions like cancers and preterm births.

10 See PhilHealth Benefits, accessed on November 22, 2019 at https://www.philhealth.gov.ph/benefits/.

11 2017/18 Macro statistics from WDI, accessed August 27, 2020; 2017 health expenditure data from WHO GHED accessed, January 6, 2020. Information on value of excise revenue is relative to overall revenue for health from government budget data representing a six year average from 2014 to 2019.

12 Paul 2020. “Presentation on India, Philippines, and Thailand for Pro-Poor Earmarking of Health Taxes for Domestic Resource Mobilization.” Domestic Resource Mobilization Collaborative, Joint Learning Network, Health Financing Technical Initiative Webinar, August 20, 2020.

13 A tax in which the amount is based on the value of the transaction.

14 US$41 is still below the average public spending on health per capita in lower-middle-income countries (LMICs).

15 See Expanded Senior Citizen Act (RA 10645).

16 Philippines, Department of Health 2018.

17 Philippines, Department of Health 2018.

18 This may be due to procurement issues

19 Philippines Department of Health, 2019

20 Temporary committee to established with the purpose of reconciling differences

21 https://www.pna.gov.ph/articles/1091709

22 Department of Finance Certification 2014-2017

23 Balances were already programmed by the DBM to various health projects including Philippines General Hospital (PhP 3.15 billion for equipping), DSWD and DepEd (PhP 5.2 billion for feeding programs), etc.

24 Refers to the baseline year prior to the first Sin Tax Incremental Revenue allocated to Health

25 Philippine GATS 2015

References

Asia Pacific Observatory of Health Systems and Policies. 2018. “The Philippines Health System Overview.” Health Systems in Transition 8, no. 2. http://apps.searo.who.int/PDS_DOCS/B5438.pdf.

Bredenkamp, C., V. Gomez, and S. Bales. 2017. Pooling Health Risks to Protect People: An Assessment of Health Insurance Coverage in the Philippines.

Cashin, C., S. Sparkes, and D. Bloom. 2017. Earmarking for Health: From Theory to Practice. Geneva: World Health Organization.

De Vera, Ben. 2019. “JTI Warns: Further Increase in Cigarette Taxes? Expect More Smuggling.” Inquirer Business, May 20. https://business.inquirer.net/270932/jti-warns-further-increase-in-cigarette-taxes-expect-more-smuggling.

Paul, Jeremias. 2020. “Presentation on India, Philippines, and Thailand for Pro-Poor Earmarking of Health Taxes for Domestic Resource Mobilization.” Domestic Resource Mobilization Collaborative, Joint Learning Network, Health Financing Technical Initiative Webinar, August 20, 2020.

Philippines, Department of Health. 2015. Global Adult Tobacco Survey: Country Report 2015. Manilla: Department of Health; Philippine Statistical Authority.

Philippines, Department of Health. 2018. Sin Tax Law Incremental Revenue for Health: Annual Report 2018. Manilla: Health Policy Development and Planning Bureau.

Philippines, Department of Health. 2019. Sin Tax Law Incremental Revenue for Health: Annual Report 2018. Manilla: Health Policy Development and Planning Bureau.

The World Bank Group. “Databank: World Development Indicators.” https://databank.worldbank.org (accessed April 15, 2021).

World Health Organization. “Global Health Expenditure Database.” https://apps.who.int/nha/database (accessed April 15, 2021).

The World Bank’s support to the Joint Learning Network for UHC is made possible with financial contributions from the following partners: