Targeted Technical Support: JLN Country Core Group and the Decentralization of Nigeria’s Social Health Insurance

By Dr. Nneka Orji-Achugo, Professor Mohammed Nasir Sambo, Dr. Kurfi Abubarker, and Olumide Olaulu Okiunola 1

Key message: The Country Core Group in Nigeria made critical contributions to the decentralization of the Social Health Insurance Scheme.

This piece is part of a series of blog posts reflecting health financing practitioner perspectives in particular countries on domestic resource mobilization (DRM) reforms and the dynamics around health financing. This work stems from the Joint Learning Network’s Dynamic Inventory of DRM Efforts. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this work reflect the views of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the World Bank, its Board of Executive Directors, or the governments they represent. Please contact [email protected] if you have an experience that you would like to share.

Health financing reform environment in Nigeria. Decades of health system underperformance driven largely by low public expenditure (Table 1) fueled momentum for the 2014 passage of the National Health Act (NHAct)—a legal framework to allocate additional resources for the health sector and define roles and responsibilities of stakeholders involved in achieving universal health coverage (UHC) (Obi 2016; Uzochukwu et al. 2018).

Table 1. Health System Performance and Financing Indicators for Nigeria

| 2010 | Recent* | ||

| Population, 2018 (millions) | 1.28 | 1.952018 | |

| Life expectancy at birth, total, 2017 | 51 | 542017 | |

| Fertility, 2017 (births per woman) | 5.8 | 5.52017 | |

| HCI score (scale of 0–1) | n.a. | 0.32017 | |

| GDP per capita, 2018 (current US$) | 2,292 | 2,0282018 | |

| Current health spending | Per capita (US$) | 78 | 752016 |

| Share of GDP | 3.3 | 3.62016 | |

| Share domestic government | 14 | 142017 | |

| Share external | 6 | 82017 | |

| Share SHI | 1 | 12017 | |

| Share out of pocket | 77 | 772017 | |

| Share of total government expenditure | Health | 2.7 | 5.02016 |

| Education | n.a. | n.a. | |

| Military | 3.2 | 4.02018 | |

Source: Data on current health expenditure (CHE) from WHO GHED 2017. Other data from WDI 2016. Data in Table 1 accessed February 24, 2019. HCI score includes measures of survival, education, and health; see HCI for further details https://datacatalog.worldbank.org/dataset/human-capital-index.

Notes: n.a. = not available; HCI = Human Capital Index; GDP = Gross domestic product; SHI = Social Health Insurance.

* Data for most recent year presented; year indicated in superscript.

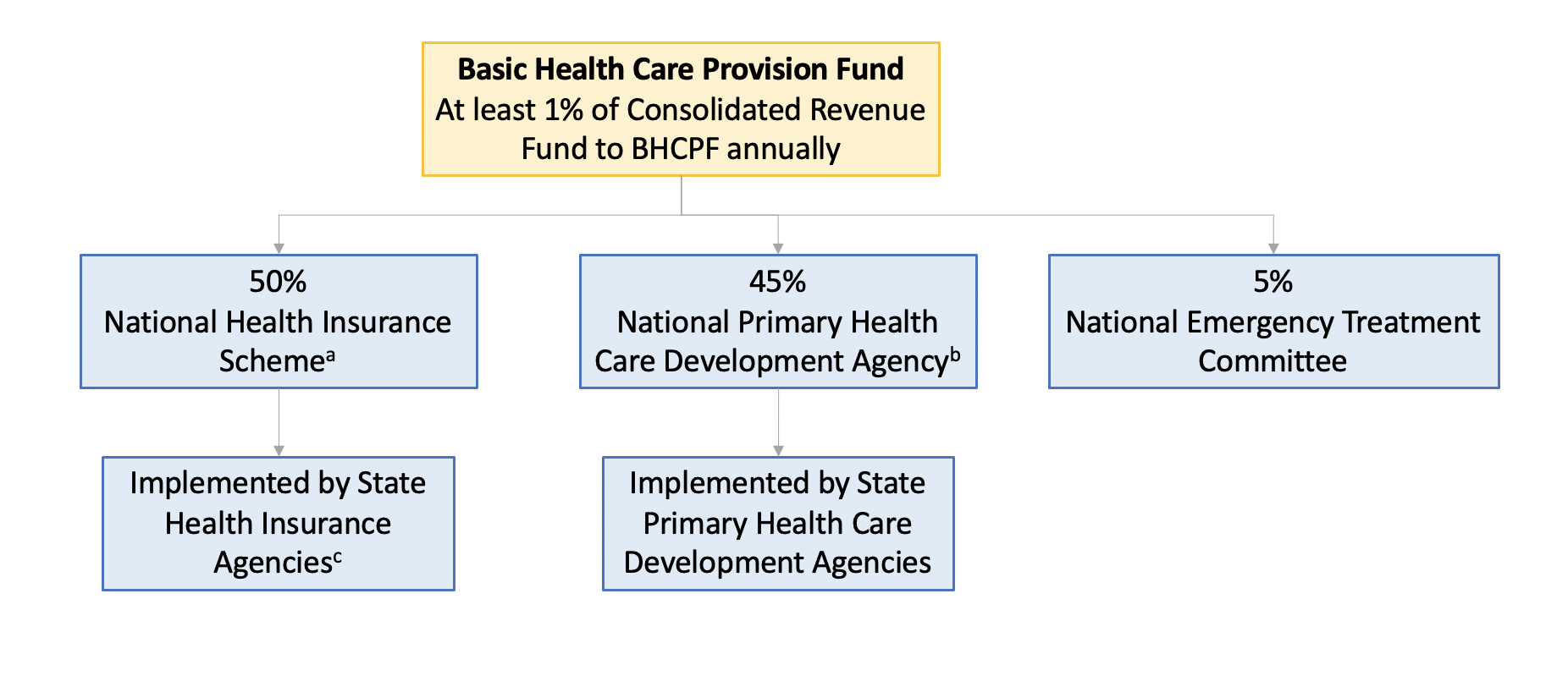

To increase overall funding for the health sector, NHAct established the Basic Health Care Provision Fund (BHCPF), an annual federal grant (Figure 1). Half of BHCPF was dedicated to fund a basic minimum package of health services across both primary and secondary levels of care through the National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS); most of the remaining fund was allocated to the National Primary Health Care Development Agency (NPHCDA) (Uzochukwu et al. 2018) to augment shortages in drugs, vaccines, manpower, and other infrastructural deficits at that level. In addition, 5 percent of the funding goes toward the provision of emergency services through the National Emergency Medical Treatment Committee (NEMTC).

In Nigeria’s decentralized health system, states were intended to be key actors in the implementation of the BHCPF. While the 2014 NHAct specified that the NPHCDA was to operate through State Primary Health Care Development Agencies, it did not define how NHIS funding was to be operationalized.

Figure 1. Structure of the Basic Health Care Provision Fund

Source: Adapted from Uzochukwu et al. 2018.

Notes:

a. To establish a basic package of services in primary health care (PHC) facilities.

b. To fund essential drugs, maintain PHC facilities, equipment, and transportation, and strengthen human resource capacity.

c. Established in 2015.

Decentralizing the National Health Insurance Scheme. The 2005-founded NHIS achieved low coverage rates by 2015 (Okebukola and Brieger 2016)—joining the health insurance scheme was not compulsory for states, purchasing structures were weak and risk pools were fragmented (Okebukola and Brieger 2016; Eke 2016). In 2015 the National Council on Health approved the decentralization of the NHIS, allowing states to set their own State Social Health Insurance (SSHI) Agencies. Decentralization aimed at creating and strengthening subnational structures to implement health insurance functions with overall guidance and regulation from the NHIS toward achieving UHC in Nigeria.

In 2015, the implementation of SSHI was unanimously adopted by the National Council on Health and reflected in policy documents such as the National Health Policy and Nigeria National Health Financing Policy and Strategy, but the specifics of design and administration were left to the states. Massive technical and capacity-building support was required by states to create and implement SSHIs in 36 states and the Federal Capital Territory.

Instituting a diverse Country Core Group in Nigeria. In the context of these major health financing reforms in 2015, Nigeria became one of the first Joint Learning Network (JLN) countries to establish a Country Core Group (CCG)—a leadership team comprising UHC stakeholders in government and partner agencies who identify critical learning needs in Nigeria to achieve UHC and determine how the JLN can meet those needs. The CCG operates with tripartite joint leadership between the Federal Ministry of Health (FMOH), the National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS), and the National Primary Health Care Development Agency (NPHCDA).

Restructuring the CCG to meet technical needs for health financing reform. The CCG supported the development of the 2016 Health Financing Policy and Strategy and the operationalization of the BHCPF. In the same year, it created a part-time CCG coordinator to enlarge its organizing capacity and expanded the CCG subnationally to meet states’ needs as they work toward UHC in a decentralized health system. The Nigeria Joint Learning Network (NJLN) presently includes 21 states of the federation.

As states established SSHI Agencies and implemented primary health care (PHC) through state primary health care development agencies, the need for knowledge exchange between states manifested. At the launch of the subnational JLN in 2017, the CCG identified that “many States are actively engaged in health care financing and primary health care system reforms—but they lack capacity and practical guidance on the ‘how-to,’” and adapted to meet this need. In November 2017, the CCG established two internal collaboratives in Nigeria based on member interest: Operationalizing State Social Health Insurance (SSHI) and Primary Health Care (PHC) Collaboratives.

Synthesizing member experience to support subnational implementation of state insurance. Setting up the SSHI Agencies required extensive stakeholder consultations, which served as the basis for commencement of the legislative processes that leads to the passing of the legislative instrument establishing SSHI Agencies. It is only after this that the agency can begin its operations. This process required an implementers’ map. Few states succeeded—with the aid of technical partners—but several struggled. The need to create a platform to support states became glaringly obvious, and the Nigeria JLN rose to the occasion.

Subsequently, the Joint Learning Network launched its Internal Technical Collaboratives in January 2018. The launch provided an opportunity for participants to reflect on challenges faced in implementing State Social Health Insurance Agencies. The outcome was a knowledge product: Design and Implementation of State Social Health Insurance in Nigeria—An Implementer’s Guide.

Oyo State stood out as a leader in implementing SSHI, having established its agency in 2017 without external financial or technical support. For this reason, the CCG hosted its SSHI Collaborative in-person in Oyo State in 2018, using the meeting as an opportunity to observe Oyo State’s SSHI Agency and inform the Implementer’s Guide’s SSHI design framework.

Through further in-person SSHI Collaborative meetings and ongoing conversations within a NJLN forum of SSHI chief operating officers, the SSHI Collaborative developed the Implementer’s Guide, which reflects challenges, innovations, and best practices of states in establishing their own SSHI Agencies.

The collaborative invited review by international and Nigeria-based Social Health Insurance experts and by states and federal agencies, and the Implementer’s Guide was finalized by FMOH and NHIS. States received soft copies ahead of the February 2019 dissemination, which was aligned with the implementation of BHCPF

Reflecting on the Implementer’s Guide’s impact, Dr. Sola Akande, the executive secretary of Oyo State Social Health Insurance Agency and key contributor to the guide said, “Every State was at a different level of implementation at that time … people were picking from the guide based on what they needed as dictated by their own level of implementation in their various States.” He noted that while states have progressed in implementation of SSHI, implementation is “still at a formative stage in Nigeria, especially in State Agencies,” and that continued peer learning can help fill the technical gaps faced by states as they progress in implementing health insurance reform. The Implementer’s Guide is now an integral part of the new reform instituted by the chief executive officer of the NHIS known as the “Health Insurance under One Roof.”

As State Social Health Insurance Agencies in Nigeria rapidly build their capacities, the convergence of strategic thinking and extensive collaboration to smoothen implementation challenges provided by CCG’s peer-to-peer environment will be instrumental in accelerating Nigeria’s universal health coverage efforts.

1 This note is lead-authored by Dr. Nneka Orji-Achugo of the Federal Ministry of Health of Nigeria with coauthors Professor Mohammed Nasir Sambo, Dr. Kurfi Abubarkar of the National Health Insurance Scheme, and Olumide Olaolu Okunola of the World Bank Group, with support from the Joint Learning Network’s Domestic Resource Mobilization (JLN DRM) Collaborative.

2 Collaboratives are an innovative collaborative learning format wherein a subset of JLN members convene on a specialized topic to exchange experience and coproduce a knowledge product with support from international experts and technical facilitators.

The World Bank’s support to the Joint Learning Network for UHC is made possible with financial contributions from the following partners:

References

Eke, Jonathan. “Decentralizing Health Insurance in Nigeria: Legal Framework for State Health Insurance Schemes.” Lecture, The Health Care Financing Capacity Building Workshop Lagos, Nigeria. June 27, 2016.

Obi, F. A. 2016. “2014 National Health Act: Slow Implementation Delays Health Benefits to Nigerians.” London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. https://resyst.lshtm.ac.uk/resources/2014-national-health-act-slow-implementation-delays-health-benefits-to-nigerians. Accessed March 12, 2020.

Okebukola, P., and W. Brieger. 2016. “Providing Universal Health Insurance Coverage in Nigeria.” Int. Q. Community Health Educ. 36 (4): 241–46.

Uzochukwu, B., E. Onwujekwe, C. Mbachu, C. Okeke, S. Molyneux, and L. Gilson. 2018. “Accountability Mechanisms for Implementing a Health Financing Option: The Case of the Basic Health Care Provision Fund (BHCPF) in Nigeria.” Int. J. Equity Health 17 (100): 1–16.

The World Bank Group. “Databank: World Development Indicators.” https://databank.worldbank.org (accessed February 24, 2019).