A Health Practitioner’s Handbook and Toolbox for Identifying the Poor and Vulnerable

Over the past decade, many low- and middle-income countries have made expanding health coverage a national priority. During 2021, 11 countries took part in the JLN Learning Collaborative on Population Targeting, which focussed on population targeting as a critical component for expanding effective coverage to unserved groups. This page outlines the key outputs and outcomes of this work.

‘Population targeting’ aims to effectively identify and reach poor and vulnerable groups – something which can be a challenge in countries with patchy data and a high proportion of informal sector workers. In these contexts, different mechanisms can be used to target the individuals and households who should be given access to particular benefits.

Targeting mechanisms represent powerful ways to maximize the impact of health spending, by directing resources to those who stand to benefit most. This might be in the form of free health insurance to those earning below a certain threshold, or with certain social and/or health characteristics (pregnant women, people with disabilities), or some other vulnerability (children and older people, unemployed or orphans).

The objective of the Learning Collaborative on Population Targeting (LCPT) was to support JLN member countries to better identify poor and vulnerable population sub-groups so as to target them with specific health programs or benefits. Participants selected two themes around which the work and associated outputs are based (click the headers for more detail on each):

(i) Institutional coordination between health and non-health agencies on population targeting ↗

(ii) Data linkage between health and non-health agencies for population targeting ↗

What is Population Targeting and why should agencies work together?

Population Targeting aims to effectively identify and reach poor and vulnerable households so as to give them access to particular social protection programs or benefits. This can be challenging to do accurately and efficiently, especially in countries with patchy data on the population and a high proportion of informal sector workers.

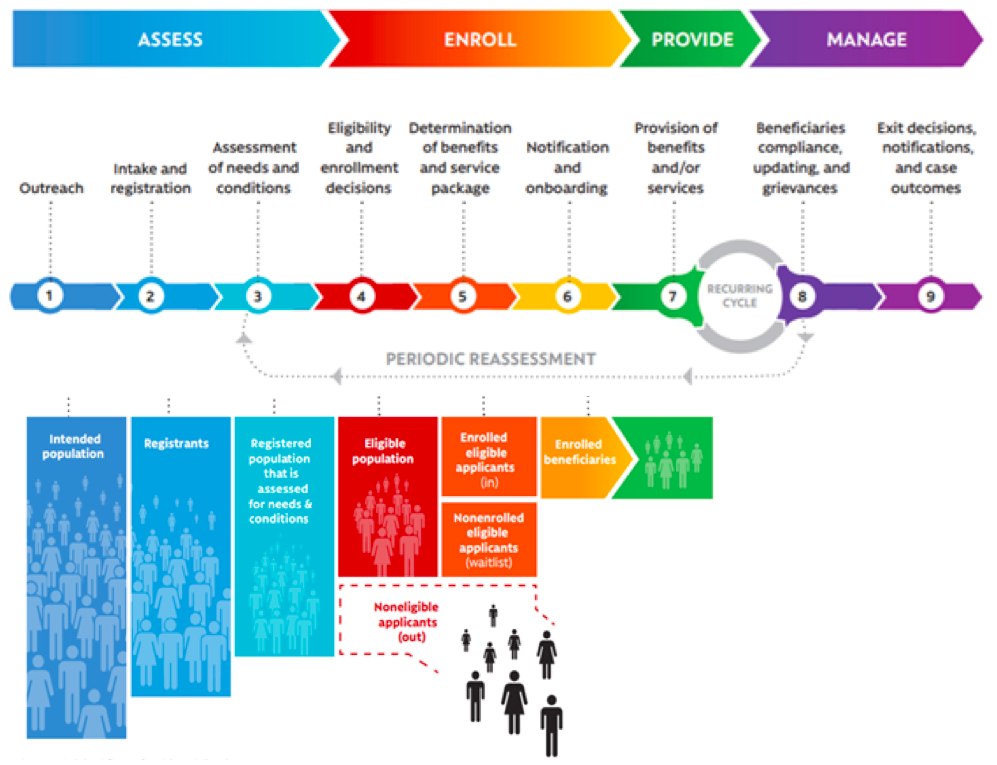

One of the most useful frameworks to understand the different components of a population targeting system is the ‘Social Protection Delivery Chain’, proposed by the World Bank in its invaluable resource Sourcebook on the Foundations of Social Protection Delivery Systems (Lindert et al. 2020). It features nine distinct stages in the process of assessment, enrollment, service provision and management of beneficiaries of any given social protection program (described more fully in the full handbook).

Countries use a variety of different methods to collect and process population targeting data, from census surveys, to active outreach and on-demand registration at local offices.

In some countries, Ministries of Health or national health insurance agencies have found themselves having to ‘go it alone’, and create their own independent systems for data collection, enrollment and eligibility assessment of vulnerable groups. This is inefficient, as other government ministries and social programs will have a similar mission to identify these at-risk populations – from cash transfer schemes and associated social registries, to tax authorities, subsidized energy or childcare programs, housing and food benefits, population identification, electoral and school registers, and many others.

In other countries, the opposite issue has arisen, and health agencies have become passive recipients of highly centralized systems for population targeting: essentially being given a list of people to enroll with no input as to how or why these were selected. This is also sub-optimal, as health agencies often have particular requirements for the data they need.

For these reasons, the core focus of the JLN Learning Collaborative on Population Targeting was how health agencies can work with others in improving their systems for population targeting, whether that is at a policy level through institutional co-ordination, or an operational level in linking data across government.

The benefits of a population targeting system in which health and non-health agencies work together effectively are numerous – both institutionally and in terms of data linkage:

-

Costs savings in having to only collect each type of data once,

-

Fewer errors through bringing together a wider range of datasets, allowing a richer understanding of who is most in need and additional sources of data validation,

-

More up-to-date data as a result of a greater number of ‘touchpoints’ between users and the state, increasing reach and public awareness,

-

Freeing up staff time from the work of eligibility assessment, processing and appeals,

-

Ability to pool resources across agencies to invest in more advanced and automated systems of population targeting, and

-

Simplifying fragmented processes from the user’s perspective, in which they have to give the same information multiple times to multiple agencies.

Beyond these direct improvements to efficiency and effectiveness, there is also an important intangible benefit to more effective population targeting. Citizens and political leaders are more likely to support further funding and reform for UHC if they see that resources are going towards those who need them most, and not being unfairly allocated or even ‘gamed’ by particular groups. Effective population targeting therefore lies at the foundation of public confidence and trust in the health system.

For more detail on these concepts and frameworks, download the full Health Practitioners Handbook on Identifying the Poor and Vulnerable.

Health Practitioner’s Handbook and Toolbox

There are two primary outputs of the Learning Collaborative on Population Targeting.

1. The Health Practitioners Handbook for Identifying the Poor and Vulnerable, which aims to help health leaders understand where their systems could improve their population targeting approach. It explains the fundamental concepts of population targeting, provides system diagnostics to understand your own level of progress against a range of dimensions, and links each area where progress may be needed to a specific tool in the Implementation Toolbox.

The entire Handbook can be downloaded at the left of this page. A French-language version is also available here.

2. The Implementation Toolbox, which offers a large, but carefully curated, library of practical documents and tools that can be used to address the specific next steps identified by the Handbook’s diagnostics. Many of these tools are new and/or previously unpublished, but best practice from previously published guidance in the social protection sector is also included.

The Implementation Toolbox is divided into two parts: 17 tools to support improved institutional coordination are available here, and 24 tools to support data linkage are available here.

The handbook and toolbox work together. Users are encouraged to use the two diagnostics in the handbook to understand where improvement is needed. You can then look up and apply the tools associated with each specific area of need.

Implementation Case Study Learning Examples

This section contains implementation examples from the Learning Collaborative’s work, focusing on Liberia and Ghana as case countries.

Liberia’s implementation case study focuses on the creation of an Inter-Agency Technical Working Group to improve coordination among population targeting reforms in three separate agencies. Click below to read the case study.

Liberia Inter-Agency Technical Working Group Implementation Case study

Ghana’s implementation case study focuses on creating a link between the national health insurance, social registry and national ID registries, enabling automatic enrollment of all the poor and vulnerable groups into health coverage. Click below to read the case study.

Acknowledgements

The production process followed an ‘implementation case co-learning’ model, in which an initial three-month period of thematic best practice workshops and task groups was followed by six months of virtual meetings in which the group supported two countries in the collaborative, Ghana and Liberia, with real-world implementations of these concepts. Special thanks go to these two country teams, whose hard work and candor were the foundation of this collaborative’s success:

From Ghana:

- Ben Kusi, Director, Membership and Regional Operations, NHIA, Ghana

- Ophelia Abrokwah, Senior Operations Manager, NHIA, Ghana

- Vivian Addo-Cobbiah, Deputy Chief Executive, Operations, NHIA, Ghana

- Prosper Laari, Head of Ghana National Household Registry (GNHR), Ghana

- David Odame – GNHR, Ghana

- Richard Adjetey, Social Protection Specialist- GNHR, Ghana

- Elizabeth o. Agyei, Logistics and Survey Information Officer – GNHR, Ghana

- Daniel Sackey, Data Analyst/Statistical Officer – GNHR, Ghana

From Liberia:

- George P. Jacobs, Assistant Minister, Health Policy and Planning, Ministry of Health & Social Welfare, Liberia

- Ernest Gonyon, Acting Director – Health Financing Unit, Ministry of Health & Social Welfare, Liberia

- Shadrach Gboki, Ministry of Gender, Children and Social Protection, Liberia

- Joseph Deema, National Identification Registry (NIR), Liberia

- Nuaker Kwenah, Health Financing Officer, MOH, Liberia

- Roland Y. Kesselly, Director, Health Financing, Ministry of Health & Social Welfare Liberia

- Aurelius Butler, National Coordinator for the LSSN / Ministry of Gender and Social Protection, Liberia

- Eric D. Mason, Database Administrator, Liberia

- Augustine F. Tokpa, Liberia Institute of Statistics and Geo Information Services (LISGIS), Liberia

Further thanks go to all the other members of the LCPT for their input and involvement throughout the 12 months of learning, implementation support and co-production:

- Dr. Almoghirah Alamin Gadasseed Abdellah, Director of Directorate General for Population Coverage National Health Insurance Fund, Sudan

- Dr Atikah Adyas, Associate Professor Lecturer in School of Health under Ministry of Health,University of Mitra Indonesia, Bandar Lampung, Indonesia

- Semlali Hassan, Consultant to the Ministry of Health, Morocco

- John Gachigi, Head Social Assistance Unit, Ministry of Labour & Social Protection, Kenya

- Christina El Khoury, Primary Healthcare Department Ministry of Public Health, Lebanon

- Esther Wabuge, Coordinator, Kenya Country Coordinating Group, Kenya

- Dr. Halima Mijinyawa, Director General of the Es Kano State State Health Insurance Commission, Nigeria

- Ademola Ade-Serrano, Innovation Manager and Digital Health Consultant, PharmAccess Foundation, Nigeria

- Susu Lin, Former Assistant Director at Ministry of Health, Myanmar

- Dr. Mohammad Abul Bashar Sarker, Attached Officer, SSK Cell, Health Economics Unit, MOHFW, Bangladesh

- Dr. Subrata Paul, PER, Health Economics Unit, MOHFW, Bangladesh

- Mona Osman, Assistant Professor of Family Medicine, American University of Beirut, Lebanon

- Ben Nkechika, Director General of the Delta State Health Insurance Commission, Nigeria

- Halima Kanini Yusuf, MOH, Kenya

- Aliyu Mohammed, Assistant General Manager, Monitoring and Evaluation Division of the National Health Insurance Scheme, Nigeria

- Njide Ndili, Country Director, PharmAccess Foundation, Nigeria

- Olakitan Jinadu, Health System Consultant, IFC, Nigeria

- Wit Yee Win, National Health Plan Implementation Monitoring Unit, Myanmar

- Rock Amegor, Director General of the Edo State Health Insurance Commission, Nigeria

- Boubacar Toure, Deputy National Director of Social Protection and Solidarity Economy, President of the JLN Mali Base Group, Mali

- Sogo Coulibaly, Head of the Social Nets Division at the National Directorate of Social Protection and Solidarity Economy, Mali

- Eka Yoshida Syofian, Hospital Manager, Pharmacist, Health Economist, MOH, Indonesia

- Rudy Kurniawan, Deputy Director of Data and Information Center, Ministry of Health Indonesia

- Dr. Simeon Onyemachi, Director General of the Anambra State Health Insurance Commission, Nigeria

Thanks also go to the technical facilitators who guided this process and inputted global expertise and additional specialist knowledge throughout many of the workshops, as well as supporting the final drafting of this output:

- Jonty Roland, Lead Facilitator

- Pip O’Keefe, Co-Lead Facilitator

- Jerry La Forgia, Co-Lead Facilitator

- Andrew Wyatt, Technical Expert – Institutional Coordination Theme

- Valentina Barca, Technical Expert – Data Linkage Theme

- Esteban Bermudez, Production Facilitation Co-Lead

- Jake Mendales, Production Facilitation Co-Lead

- Maddie Lambert, Production Facilitation Co-Lead

The handbook and toolbox were co-produced by the Learning Collaborative on Population Targeting, an initiative of the Joint Learning Network on Universal Health Coverage (JLN). Here you can see the names of all those who contributed to this work.